ARCHIVES

In addition to her filmmaking activities, Vivian Ostrovsky was a pioneer in curating, distributing and promoting women’s cinema from the mid 1970s onwards. In June 1974, she co-organised, with the curator Esta Marshall, one of the first feminist film festivals in France, (alongside ‘Musidora’, also held in Paris in 1974), showcasing the work of US-based women: ‘Women by Women’, at the American Cultural Centre in Paris. Underestimated and neglected by a male-dominated industry, many of those who participated in the festival asked Ostrovsky and Marshall to hold on to the prints to see if they could get them shown elsewhere. The huge difficulties women faced in distributing their films were immediately evident, and Ostrovsky and Marshall subsequently organised the international festival ‘Femmes/Films’ the following year, supported by the FNAC cultural association, Alpha FNAC. Open to women only, it was the first festival in Paris to centre discussions on female homosexuality. Ostrovsky and Marhsall then created the organisation Femmes/Media with its stated objectives to organise festivals of women’s films and to create a hub and information centre for, for the first time, ‘all those women working behind, in front, or next to the camera’. In 1975, the ‘Year of the Woman’ as declared by UNESCO, they held an international symposium in a luxury hotel at St. Vincent, Italy, sponsored by UNESCO, in which outlines for women working in film were created, discussed and debated; amongst the participants were Mai Zetterling, Susan Sontag, Chantal Akerman, Agnès Varda, Marta Meszaros, Atiat El Abnoudi, Faten Hamama… A collectively authored text declares: ‘we refuse prestige, political recuperation and false seriousness. We seek to show what women’s solidarity looks like when they choose a dialogue based on their specific experiences.’

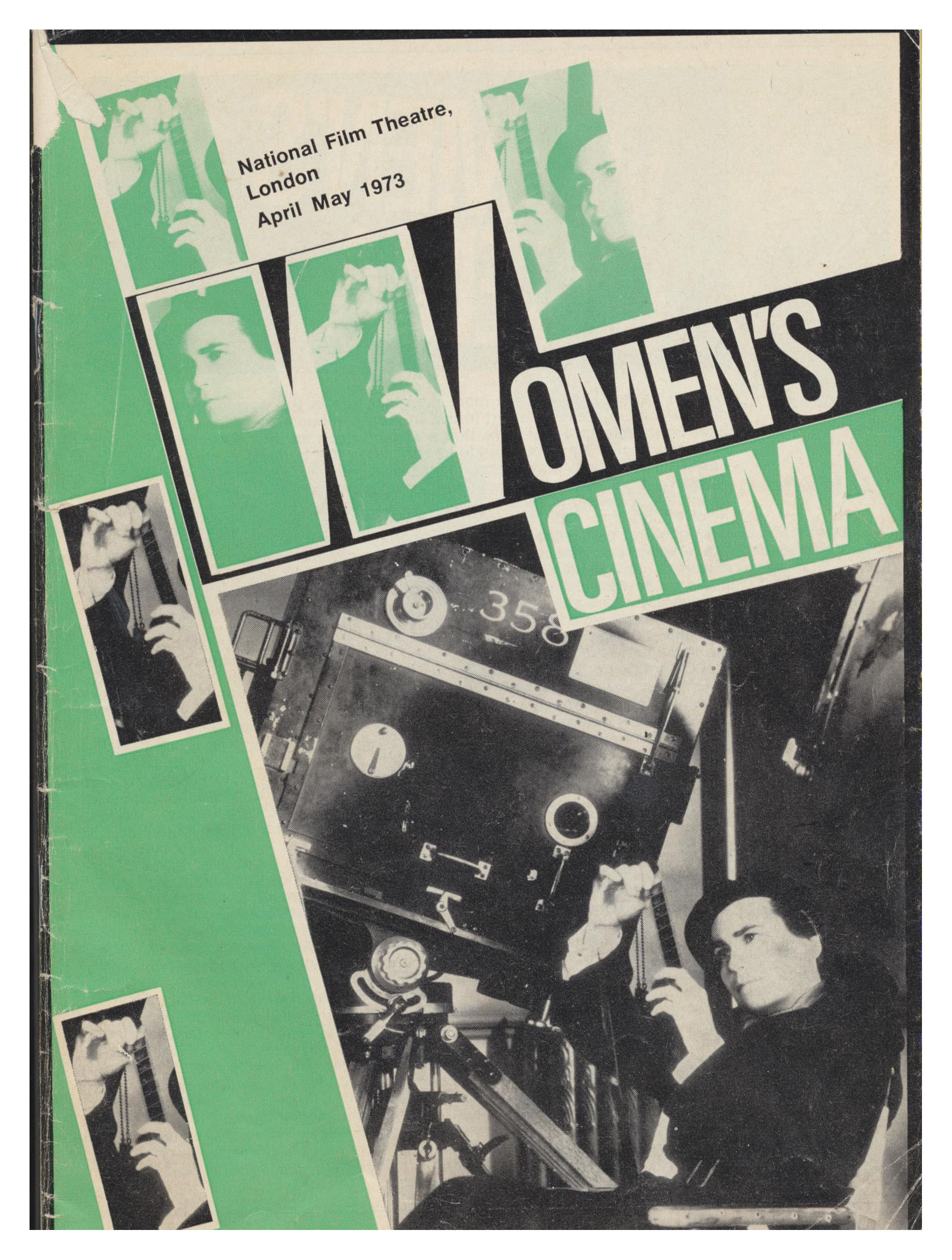

It’s impossible to underestimate the importance of this work in its commitment to all those women working in cinema: whilst feminist journals such as Camera Obscura, Women & Film, and Screen, publishing the work of feminist film critics such as Laura Mulvey and Claire Johnston, sought to revolutionise both the image of women in the cinema, and the analysis of that image, it was never forgotten that there were also those working behind the scenes to make this work visible, to make it possible, and bring to it to audiences. Discussion, debate and analysis was central to the works Ostrovsky and Marshall were showing and the way in which they were shown. As the editorial of the first issue of Women & Film stated, ‘we want to take charge over our minds, bodies and images’. It was clear from the start that this was a collective endeavour. Out with the auteur industrial complex, and in with working together, celebrating those who have been made invisible, recognising that the image of women onscreen can only be transformed through breaking down the hierarchies of traditional film production and distribution.

In 1976, building on the work of Femmes/Media, Ostrovsky and Roseau Grange founded Ciné-Femmes International, a DIY international distribution network run largely from an old jalopy, a Renault 4L, stuffed full of film reels, video tapes and the like, with Ostrovsky and Grange driving all over Europe to women’s festivals and international film festivals such as Kinomata in Rome (1976), Copenhagan Women’s Film Festival (1976), the Le Nemesiache organised feminist film festivals in Sorrento and Naples (1976, 1977,1978), San Sebastian (in 1978), Berlin Arsenal (1978), and many more. What was unique about the selection of films these festivals promoted, and that Ostrovsky and Grange distributed, was that they defied categorisation other than as feminist works: experimental art films on 8mm could be found next to 35mm prints, documentaries made on Portapak alongside feature-length fiction films. They showed works at youth centres, cine-clubs, festivals, the network of Maisons de la Culture. This was a labour of love, with no grant money, Ostrovsky and Grange scraping by through journalist work (Grange at Art et Décoration, Ostrovsky at Charlie Mensuel) and translation (paid peanuts, the two were responsible for the first French translation of Charlie Schultz’s Peanuts).

At the forefront of international networks of women’s filmmakers and festivals, Ostrovsky, Grange and Marshall’s work was crucial in bringing women filmmakers, programmers and audiences together across France and Europe, paving the way for later festival such as the Créteil International Women’s Film Festival, which was initiated by Elizabeth Tréhard and Jackie Buet in 1979. Ostrovsky, Marshall and Grange brought the films of Carolee Schneemann, Barbara Hammer and Maya Deren to audiences in Europe, as well as promoting filmmakers like Chantal Akerman, Agnès Varda, Marguerite Duras, Jackie Raynal, Maria Lassnig, Safi Faye, Sarah Maldoror, Maria Klonaris and Katerina Thomadaki, feminist video collectives such as Vidéo Out and Les Insoumuses… the list goes on. Recognising the need for a revolutionary, new, feminist imaginary, they connected the women’s movement across Europe, brilliantly, tirelessly, creatively responding to that urgent demand for self-representation on women’s own terms.

Ros Murray

Dr Ros Murray is a lecturer in French at King’s College London and a co-founding member of the research network Herstoriographies .

Her current research project focuses on feminist documentary video in 1970s France, exploring the relationship between video technologies, embodiment and politics.